Assessing the Variants and the Reliability of the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaᵃ)

Published on: October 26, 2025

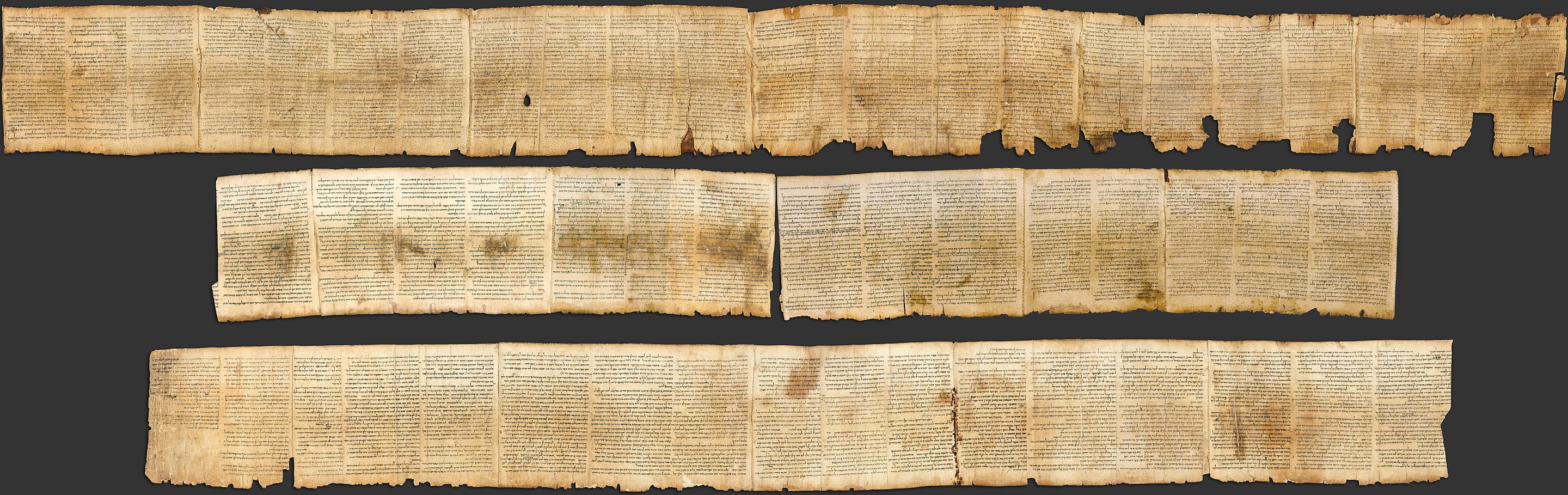

The Great Isaiah Scroll from Qumran Cave 1, one of the oldest complete copies of Isaiah (ca. 150 BCE)

Introduction

In this in-depth interview, Dr John Meade Old Testament textual critic and co-author of Scribes and Scripture joins Wesley Huff to clarify widespread misunderstandings about the Dead Sea Scrolls and their relationship to the Masoretic Text (MT) of the Hebrew Bible.

A recent viral claim (Joe Rogan and Wes Huff) suggested that the Great Isaiah Scroll (1 Q Isaᵃ) is “word-for-word identical” with the MT. While there is remarkable correspondence, Meade cautions that such wording is inaccurate and that the nature of textual variants must be understood before numbers are quoted. Wes Huff acknowledges this correction.

The discussion explores how the Hebrew text was transmitted, what constitutes a variant, and why the Dead Sea Scrolls actually confirm the fidelity of the Masoretic tradition rather than undermine it.

Historical Context

The Masoretic Tradition

The Masoretes (8th–10th century AD) were Jewish scribes who meticulously copied the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible and devised the system of vowel points (niqqud) and cantillation marks to record oral tradition.

They did not invent the wording but standardized the reading tradition.

They also transitioned from scrolls to the codex format, enabling easier collation and comparison.

The Masoretic manuscripts—such as the Aleppo Codex and Leningrad Codex form the base of all modern Hebrew Bibles and most English Old Testament translations.

The Great Isaiah Scroll (1 Q Isaᵃ)

Discovered in 1947 in Qumran Cave 1, the Great Isaiah Scroll is one of the first and most complete biblical manuscripts among the Dead Sea Scrolls, dated ca. 150 BCE—about a thousand years older than the earliest complete Masoretic copies.

It provides a direct look at the Hebrew text of Isaiah before Christ.

Despite its age, its text is substantially the same as the medieval MT, demonstrating the stability of transmission across a millennium.

The Numbers Problem: Counting Is Subjective

Meade underscores that counting “variants” or “words” in Hebrew is not straightforward:

- Hebrew words can contain prefixes and suffixes (e.g., pronouns attached to verbs).

- Depending on whether software or scribes separate these units, totals can differ by thousands.

- For instance, some software counts over 22,000 words in Isaiah; Masoretic counting yields ~17,000.

When scholars report that 1 Q Isaᵃ and the MT have “92 % agreement,” they often fail to define what counts as:

- a word, and

- a variant (does spelling count? orthography? missing preposition?).

Thus, statistics without definition mislead.

As Meade says: “Counting is subjective.”

Categories of Variants

| Type | Example | Nature | Impact on Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthographic / Spelling | דוד (DWD) vs דויד (DWYD) – “David” | Updated spelling conventions (Qumran inserted an extra yod) | None |

| Phonological / Linguistic | Isa 58:2 – MT אֱלֹהָיו (’eloḥāyw) vs 1 Q א�ֱלֹהֹו (’eloḥō) | Contracted suffix vowel | None |

| Prepositional Variation | עַל (ʿal, “on/upon”) vs לְ (lĕ, “to/for”) | Interchangeable Hebrew prepositions | None |

| Morphological Simplification | Loss of “waw consecutive” forms (e.g., Isa 8:21) | Grammatical modernization | None |

| Scribal Error: Par lepsis | Isa 40:7–8 – omission of ~12 words | Scribe’s eye skipped identical phrase | Corrected later; MT preserves original |

| Substantive (Meaningful) | Isa 2:9b–10 – MT includes “Do not forgive them” omitted in 1 Q | Potential theological difference | MT likely preserves original harder reading |

Orthography and Qumran Spelling Practice

The community at Qumran developed a characteristic orthography (QSP = Qumran Spelling Practice), often inserting mater lectionis (letters functioning as vowels) to clarify pronunciation.

Thus, 1 Q Isaᵃ shows “updated” spellings, whereas the MT preserves the older consonantal forms.

These are not new readings, merely later spellings.

Case Studies in Detail

1. Isaiah 40:7–8 – A Classic Par lepsis

The MT reads:

“The grass withers, the flower fades, because the breath of YHWH blows upon it; surely the people are grass.

The grass withers, the flower fades, but the word of our God stands forever.”

1 Q Isaᵃ omits the first of the two repeated lines.

Reason: the scribe’s eye skipped from the first “the grass withers…” to the second occurrence, omitting 12 words.

Later correction in the scroll’s margin restores the missing line.

→ Result: a scribal error, not a different text tradition.

2. Isaiah 4:5–6 – Damage to Exemplar

In chapters 34–66, 1 Q Isaᵃ shows regular omissions at column bottoms.

Dr Drew Longacre’s study demonstrates that the exemplar used by the scribe was physically damaged at those points—likely where the scroll rested on a shelf.

These gaps explain missing lines without invoking theological or literary development.

→ Result: physical deterioration, not variant theology.

3. Isaiah 2:9b–10 – “Do not forgive them”

Here the MT includes a difficult phrase: אַל־תִּשָּׂא לָהֶם — “Do not forgive them.”

1 Q Isaᵃ omits it entirely.

Scholars debate:

- Eugene Ulrich: omission suggests MT added the line (developmental growth).

- Dominique Barthelemy, Hugh Williamson, Marvin Sweeney, and Meade: MT preserves original hard reading.

- Scribes soften difficult texts, not create them.

- Several later scrolls and the Septuagint likewise soften the harshness (“You will not forgive…”).

→ Result: MT likely original; 1 Q omission a deliberate theological smoothing.

Evaluating the “92 % Agreement”

Meade argues that if one removes:

- purely orthographic and phonological differences,

- interchangeable prepositions, and

- errors caused by damage or par lepsis,

then the actual semantic correspondence between 1 Q Isaᵃ and MT rises well above 95 %, possibly 98–99 % identical in meaning.

Such consistency over a thousand years defies the “telephone-game” analogy often invoked by skeptics.

The scribal culture of antiquity valued precision; errors were rare, often noted, and corrected.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Analysis

A quantitative count (“2800 variants”) tells little about significance.

A qualitative study asks:

- Does the variant change meaning?

- Can it be explained by normal linguistic development?

- Is there evidence of correction?

Only a handful of cases across 66 chapters of Isaiah involve genuine uncertainty about original wording.

Therefore, variant lists in Discoveries in the Judean Desert 32 should be read as catalogues of differences, not judgments on meaning.

Scholarly Disagreement and the Myth of “Consensus”

The interview warns against invoking “the scholarly consensus” as a rhetorical weapon.

Even among leading textual critics—Eugene Ulrich, Emanuel Tov, Drew Longacre, Hugh Williamson, Dominique Barthelemy—opinions differ on direction of change and methodology.

There is broad agreement that the Masoretic tradition is reliable, but not unanimity on every verse.

True scholarship involves weighing evidence, not repeating slogans.

Implications for Scripture and Transmission

- Stability: The Hebrew text of Isaiah remained remarkably consistent for over a millennium.

- Transparency: Ancient scribes acknowledged and corrected their own mistakes; margins and corrections show an awareness of textual fidelity.

- Complexity: Textual criticism requires linguistic, material, and historical awareness—statistics alone mislead.

- Trustworthiness: Variants show human transmission, not corruption of message. The prophetic message remains intact across all witnesses.

- Scholarly Humility: Terms like “identical,” “consensus,” and “variant” must be defined with rigor.

Representative Table: Classes of Variants

| Class | Typical % of total | Description | Example | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthographic | ~60–70 % | Spelling differences (mater lectionis, vowels) | דוד vs דויד | None |

| Linguistic/Phonological | ~10–15 % | Contractions, suffix adjustments | אלֹהֹו vs אלֹהָיו | None |

| Grammatical (prepositions, word order) | ~10 % | Slight syntax difference | על vs לְ | None |

| Scribal (par lepsis, dittography) | ~5 % | Copyist slips, corrected | Isa 40:7–8 | Minor |

| Meaningful (potentially theological) | < 1–2 % | Require judgment of original | Isa 2:9b–10 | Sometimes debated |

Concluding Observations

From a scholarly standpoint, the comparison between 1 Q Isaᵃ and the Masoretic Isaiah provides one of the strongest demonstrations of textual preservation in ancient literature.

- The overwhelming agreement confirms the fidelity of Jewish scribal transmission.

- Where differences exist, they are mostly predictable by linguistic evolution or human scribal behavior.

- Assertions of “radical textual fluidity” or “developmental accretion” are overstated and rarely sustained by data.

In short:

The Great Isaiah Scroll does not undermine the Masoretic Text—it vindicates it.

The debate reminds us that statistics without interpretation are meaningless, and that careful qualitative analysis reveals a text transmitted with extraordinary care and accuracy.

References & Further Reading

- Wesley Huff & John Meade, Interview on the Great Isaiah Scroll (Apologetics Canada Podcast, 2024). Setting the record straight on the Great Isaiah Scroll | Wes Huff & Dr. John Meade

- Eugene Ulrich & Peter Flint, Discoveries in the Judean Desert XXXII: Qumran Cave 1 – The Isaiah Scrolls (1QIsaᵃ, 1QIsaᵇ). Oxford: Clarendon, 2010.

- Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, 4th ed. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2021.

- Dominique Barthelemy, Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament: Isaïe, Göttingen, 1986.

- Hugh G. M. Williamson, Isaiah 1–12 (ICC). London: T&T Clark, 2021.

- Drew Longacre, “Material Damage and the Exemplar of the Great Isaiah Scroll,” Textus 34 (2022): 23–45.

- John D. Meade & Peter J. Gurry, Scribes and Scripture: The Amazing Story of How We Got the Bible. Wheaton: Crossway, 2022.

- Anthony Ferguson, “Non-Aligned Texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls” (PhD diss., University of Birmingham, 2020).